By David Drickhamer

11/23/2016

A manufacturer of highly engineered marine products sets ambitious targets for improving quality and on-time delivery, and achieves them in record time.

“A full lean transformation takes time. It’s like turning around an aircraft carrier.” So goes conventional wisdom.

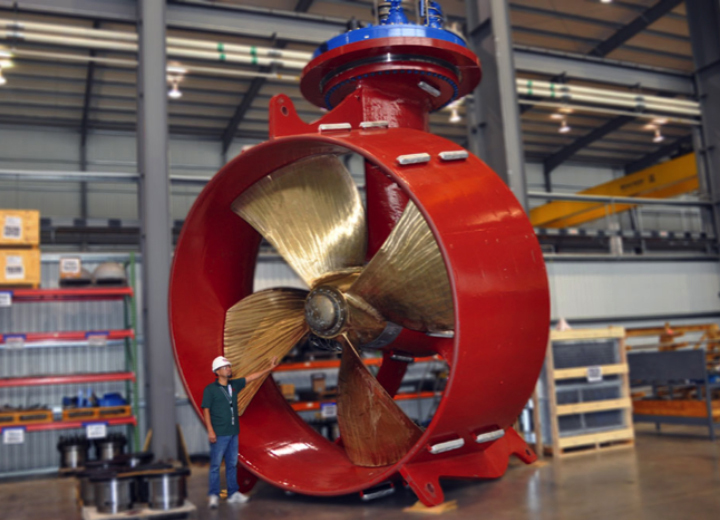

Thrustmaster of Texas manufactures heavy-duty thrusters that range in size from 35 hp to 8,000+ hp. The thrusters can rotate 360° around a fixed axis, making it possible for ships and other vessels to maneuver and turn around quickly. Perhaps it’s not surprising then that the Houston-based manufacturer didn’t take long to turn around its operations after implementing lean management practices.

Over the course of 18 months Thrustmaster streamlined its work and material flow, increased on-time delivery to 100% and widened profit margins. Today, the company’s production operations can scale with market demand, a critical advantage in the boom-and-bust oil sector, which accounts for a large portion of their business. The changes in cost structure are also opening up new market opportunities.

This Lean Enterprise Institute (LEI) case study reveals how Thrustmaster successfully adopted lean practices and made sustainable improvements in a short period of time, and how other manufacturers of highly engineered, low-volume products can follow their lead using the Lean Transformation Framework (LTF).

From observing transformations for nearly 20 years and working closely with companies through the Co-Learning Partners Program, LEI has found that successful transformations require a situational approach in which companies create their own unique journeys.

While each journey is different, successful ones share common traits of thinking and acting differently in five key dimensions, expressed as questions:

Thrustmaster of Texas at a Glance

- HQ & Operations: Houston

- Products: Azimuth Thrusters and other propulsion units

- Markets: Offshore, military, inland tow boats, other marine applications

- Employees: 250-300

- Revenues: $100-150 million

- What is our purpose?

- What value do we create, or what problem are we trying to solve?

- How do we design and do the actual work?

- How do we identify and develop the capabilities we need?

- What management system and leadership behaviors are required to support the new way of working

Years of Rapid Growth, and Growing Frustration

During the 2000s, sales at Thrustmaster grew 10-fold and the total number of employees increased seven-fold. In 2008 it made Inc. magazine’s fastest growing companies list, reporting a three-year revenue growth of 1,400%. The following year, to keep up with demand, the company added 200,000 sq. ft. to its factory.

As exhilarating as it is, such growth can hide a lot of problems. Then again, the problems may be painfully obvious. For Thrustmaster their main issue was on-time delivery, which hovered around 20%.

No matter what they tried orders were always running late. The scheduling module in their ERP system didn’t help. A new advanced planning and scheduling system didn’t help. Neither did investments in more advanced machinery. To get orders out the door they kept hiring more people and increasing overtime.

Thrustmaster president and owner Joe Bekker attributes their challenges during this period to both the rapid growth and the inherent differences between running a small and mid-sized organization. Their expansion decentralized communications and created departmental silos, he says, which led to finger pointing whenever issues popped up.

Frank Montemayor, continuous improvement manager for Thrustmaster of Texas, described the manufacturer’s transformation during a session at LEI’s Lean Transformation Summit March 18, 2016, in Las Vegas.

In mid-2013, following many attempts to rein in operations, Bekker sat down with a representative from one of their software vendors and asked why, after investing millions of dollars, they still weren’t seeing any improvements in their on-time delivery rates. With little hesitation, the consultant said, “Software is not your problem.” He said the problem was the company’s production processes, and recommended that Bekker read Lean Thinking, the introduction to lean manufacturing principles and practices written by LEI’s Jim Womack and Dan Jones, first published in 1996.

Frank Montemayor, continuous improvement manager for Thrustmaster of Texas, described the manufacturer’s transformation during a session at LEI’s Lean Transformation Summit March 18, 2016, in Las Vegas.

In addition to being huge—the propeller alone on the company’s largest thruster is over 14 feet in diameter—all of their products are custom engineered. Thrustmaster’s highly complex, customized product mix did not correlate well with most of the examples in Lean Thinking. But there was one exception: Lantech, the Louisville-based maker of pallet stretch-wrapping machines. In the Lantech case study Bekker and his leadership team saw a similar type of product—highly engineered for specific applications, one- or two-unit order quantities—and a mirror image of the problems they were having with order management, scheduling, quality, and delivery.

So Bekker called Jim Lancaster, then president of Lantech, and asked if they could come up to Kentucky and take a look at his facility. Lancaster said that they could visit someday, but that seeing his facility as it is today would be like trying to learn how to become a basketball player by watching a player slam dunk. They needed to learn how to dribble first, he said, and demonstrate that they were serious about applying lean principles at Thrustmaster.

Going to Disney

As recounted in Lean Thinking, Lantech’s lean journey was prompted by a crisis. The company had lost a patent infringement suit against a competitor selling clones of its machines. By the early 1990s orders were declining and it was losing money.

In Thrustmaster’s case, financially speaking, they were doing quite well in 2013. Despite the economic downturn a few years before, they had a healthy backlog of projects. Other than chronic late deliveries and some quality issues, the company wasn’t struggling. Profitability was good and there was no overt “burning platform” for change.

Adding to the change management challenge was the fact that company leaders, after doing their research about other successful lean implementations, wanted to transform the whole company. “When we first said we were going to do lean, we knew we had to do it everywhere,” recalls Jason Small, general manager. “People said to just focus on assembly, but that wasn’t good enough for us.”

David Wesphal, brought in by LEI to support the transformation, understood the implications of such ambitions from his experience turning around plants at GM and auto part maker Delphi. He helped the Thrustmaster leadership team and employees both appreciate the breadth of the challenge, and visualize what the future might look like.

“Starting from our home in Michigan, if I had told my kids that we were going to get in the car and drive for three days to get to an amazing place called Disneyworld, they might be happy enough on the first day,” explains Westphal. “But by day two of being in the car all day, if I didn’t do a great job of explaining what Disney is, their enthusiasm would have worn off.”

A lean transformation is a lot like that, he says. You’re going to a wonderful place, but many people have had a bad experience with the “lean” terminology, or don’t understand where the company is going. “The car ride is going to be tough, and how people do their jobs will change. That’s why you have to help everyone understand that you’re going to a really great place,” says Wesphal.

Where to Start?

Company leaders didn’t start communicating this grand vision for the future without first doing some preparation. With the help of LEI coaches from LEI’s Co-Learning Partnerships program, they created an 18-month strategy deployment plan focused on manufacturing that would address the company’s quality, delivery, and cost issues (in that order). Then a team developed a value stream map for one of their key products. The original intention was to set up a model work cell. Then, somewhat fortuitously, the order volume dropped for the product they had mapped.

“We realized that the model line approach wouldn’t work for us,” says Frank Montemayor, continuous improvement manager “So we divided the shop based on product size, and developed the cell layout and standard work based on key assembly processes. Today we can run a variety of models through the same two cell layouts.”

Setting up the two groups of assembly cells (one for units 500 hp or less, and the other for 500 hp and higher) introduced the “basic thinking” noted in question five above. These foundational principles would guide the rest of their lean implementation work: (1) Establish line-of-sight visual controls, (2) Create and enforce standard work, (3) Improve workplace organization, and (4) Move everything forward based on the established takt time.

Prior to the lean rollout, there were few standard processes, and it was impossible to see the material flow, according to Montemayor. You couldn’t walk the material flow or distinguish work-in-process from other inventory that happened to be sitting around. It was impossible for managers to distinguish normal from abnormal situations, or know if a particular unit was ahead or behind schedule.

To help expose the unseen opportunities, Montemayor and another employee created a spaghetti diagram that tracked the 300 steps required to put together one product, a hydraulic rotating group, over the course of four days. Walking around the facility—mostly to retrieve parts and materials—added up to seven miles and nearly 10 hours of nonvalue-added time. (This compares to a total cycle time of 10 hours for the same assembly today.)

Such revelations and the early gains in the new work cells helped everyone begin to understand the potential benefits from applying lean practices. The change initiative officially began with several company-wide meetings where Bekker and other managers talked about the strategic direction of the organization. They also communicated management’s 18-month goals, which answered the first lean transformation question: What problems are we trying to solve? Those goals were:

- Improve first-pass yield to 90%,

- Increase on-time delivery to at least 90%, and

- Reduce product costs to 100% or less of targets.

Leadership began to work on the company’s culture by emphasizing their commitment to the lean transition, and explained how it could impact everyone’s work.

“A lot goes on behind the scene of a successful lean transformation that no one talks about,” Westphal explains. “At the end of the day, lean transformations succeed or fail because of people.”

In addition to communication, the people side of their lean implementation (the focus of transformation question three), included education and organizational changes. During the kickoff phase, Thrustmaster employees attended classes at the University of Houston where they learned fundamental lean principles and tools. As the effort unfolded the company also removed some management levels to further streamline communications. The company was able to redeploy some, but not all, of the managers.

Propelled Forward

In 1984 Thrustmaster shipped its first marine propulsion unit for the Army Corps of Engineers. The privately held company grew slowly but steadily through the 1980s and 1990s, selling a variety of highly engineered products for military and commercial applications on ferries, barges, cruise vessels, casino boats, tug boats, offshore drilling platforms and ships.

As it grew Thrustmaster expanded, adding significant square footage to its manufacturing facility in 2002 and again in 2009. Sales exceeded $150 million in 2011 but have since contracted with the declines in petroleum prices and exploration, which has dramatically reduced new equipment orders.

Creating Flow, Standard Work, and Visual Management

Like any job shop, the assembly process at Thrustmaster had always been highly dependent on employees’ tacit knowledge and experience. Setting up the work cells supported management’s goals to become more of a custom manufacturer than a job shop, and thereby improve quality. Today, while the steps required to assemble each unit are roughly the same, the details in each job router (which can run over 100 pages) will vary based on the customer’s application and specifications.

Thrustmaster Assembly Area Organization

Before

Before Thrustmaster reorganized the assembly area the work flow was not visible, work areas were not defined, and there was no standard work. Managers could not distinguish between work-in-process (WIP) and finished goods and could not see the work status or labor resources required for each operation.

After

After reorganization the work areas and incoming material locations are clearly defined. Finished product flows (is pulled) by the next operation and WIP is easy to see and count. The new flow cells run on a three-day pitch, meaning that a drive is built every three days. Material moves every three days to the next workflow where the cell team builds in work groups with specific tasks and takt times. Quality is built into each team time element, eliminating wait times and waste from support functions.

To address question two of the transformation framework—how the actual work is designed, performed, and improved—the Thrustmaster team setup the cells and captured some of that tribal knowledge. The first thing employees did was record exactly how they put together each product. Those steps were then used to create standard, time-based work sequences that streamlined the work processes and material flow. (Montemayor describes some of the results in this video clip:

The flange mount for a 6,000-hp thruster, for example, is made up of 1,200 components. Previously, it would take 8-10 days to put one unit together, if everything went well and the assemblers had all of the parts they needed. Doing some of the work in parallel, instead of in series, and making other process refinements has since reduced the time required to assemble the component down to 24 hours.

Setting up the work cells and creating standard work revealed where they had too many people working, or too few. It freed up floor space and improved material flow, and made it possible to recognize recurring problems and get at root causes. Without leaving the cells employees began communicating issues to supervisors using a flag system—red for offline, blue for material shortage, orange for supervisor required, and so on—and recorded the causes on white boards. It didn’t take very long after they began tracking such issues to see that material availability was a major problem.

Today, tools and other materials are housed in lockers with shadow boards in each cell. Material handlers pick and deliver all of the parts required for each work order on carts with peg boards mounted on the sides. In the past, to find what they needed, assemblers would have to scrounge through a jumble of parts hidden in small boxes on a pallet. Now, the parts are clearly labeled and sequenced in the order that they will be needed to assemble each product.

Part Presentation

Before

For each job assemblers used to have to search through a jumble of parts hidden in cardboard boxes. Today, material handlers deliver all of the parts and fasteners in sequence on carts with peg boards mounted on the sides.

After

In addition to saving hours looking for the right parts, the new part delivery system makes it possible for anyone to see at a glance the assembly status of each unit. The warehouse itself was also reorganized around the way parts are typically pulled and sequenced, and less so by part size or type.

“The assembly process today is much more respectful of our workers,” says Montemayor. “Each operation has all of the parts they need in a single bag. There should be nothing left over. It’s easy to see what to do next.”

Throughout the Thrustmaster facility, visual management practices make it easier for managers to determine when a unit is ahead or behind schedule, to see abnormal situations, and take countermeasures when necessary. The communication goes both ways. The business’s key performance indicators—quality, on-time delivery, schedule attainment, costs per project, etc., none of which had been shared previously—are tracked and reported for everyone on the floor to see.

“I like to call it ‘visual flow,’” says Westphal. “People have to be able to see whether they’re winning or losing at a glance. They need to know if they’re having a great day or a bad day. They didn’t know that before.”

Visual Management

Here are just some of the visual management tools used by Thrustmaster of Texas.

Operations KPIs

Quality, on-time delivery, 5S, schedule attainment, PO on time %, cost/unit/project %, budgets/WC, direct vs. indirect labor

Assembly Schedule

Machine Schedule

Visual Schedule

Workcell Status Flags

Manufacturing kanban

In addition to material flow, visual control boards are used to manually create and adjust machine, assembly and job schedules. In the past the machining and assembly departments relied on a sophisticated scheduling system that released orders to the floor based on material delivery dates.

“These software systems have very complex algorithms, but that doesn’t matter,” explains Westphal. “You’re never going to build what you can’t walk into the cell at 7:00 a.m. and put your fingers on. It doesn’t matter what your scheduling system says.

“They had put a lot of time and effort into that system, everyone was afraid of shutting it off,” he continues. “That slowly went away after we made their material flow visual and stopped using the system for anything more than a baseline scheduling tool.”

Moving People to the Gemba

When it comes to leading a lean transformation, there’s a difference between leaders “supporting” the changes and creating an environment where there aren’t any other options. By multiple accounts, the lean implementation at Thrustmaster began slowly. Too slowly, in fact, if they had any hope of hitting their 18-month targets.

From the beginning the effort had strong support from company President Joe Bekker and General Manager Jason Small. As a 300-employee, privately owned company with one location, they benefitted from little bureaucracy and a flat organizational structure. But there were still departmental divisions, and years of entrenched behavior and ways of doing things that would start to change as the company addressed question four: What management system and leadership behaviors are required to support the new way of working?

Eventually, everyone got management’s message: The company would no longer be defined solely by how well it designed and engineered thrusters, but also by the quality and on-time delivery of by the units they manufactured and shipped. From that perspective the fundamental responsibility of all employees is therefore to support manufacturing and final assembly. After all, if nothing ships on any given day, the company doesn’t make any money.

Going to the Gemba: Less Walking, Less Waste

Like a lot of lean manufacturers, the management team at Thrustmaster of Texas (Houston) goes out to the factory every morning to talk with production team leaders about the day’s challenges and issues. Participants include the company’s general manager, CI manager, manufacturing manager, purchasing manager, buyers, warehouse supervisor and others.

Problem Solving Team Board

When they started their lean journey, they walked around to each department to review the individual performance boards displaying current metrics, problems and proposed solutions.

They have since cut the time required for these daily reviews in half and improved cross-department communication by holding the daily management review at one location in front of a giant 30 x 12-foot performance board (above).

“It was great visiting every department every day,” says Jason Small, General Manager. “But it took an hour. We’ve reduced our daily meeting times down to 20-25 minutes with the same effectiveness.”

Leadership reinforced that core focus by starting to hold staff meetings on the production floor. Small and Montemayor started leading daily management walks through the plant as well. But the message really took hold when they moved some people out to the floor, including the scheduling and purchasing departments, manufacturing engineers, and a rotating design engineer position. That immediately accelerated the pace of change.

For example, as noted above, material availability was the number one cause of delays in assembly, but purchasing didn’t know if incoming material was arriving on time. So management moved the purchasing team’s desks out to the receiving dock along with status boards showing every active PO organized by delivery day.

“At the end of the first day we looked at how many of the 14 orders that were supposed to come in actually arrived,” recalls Small. “The answer was ‘none.’ So they started calling our vendors. Until we put them out there on the dock, they never had that urgency.

“Within a month the purchasing team had created processes that pulled in all incoming material on its due date,” he continues. “When we started there were probably 20-25 exceptions in receiving every day. Now, there might be two or three over a two-week period.”

Such moves and the subsequent improvements reinforced the value of the changes during the first few months when a new lean initiative often feels like it’s just creating more work for everyone. Old-fashioned incentives helped with the rollout as well.

Not long after they setup the work cells a major customer accelerated delivery of a 50-unit order. To encourage the team to hit the takt times and new ship dates, management offered project team members box seats to a Houston Rockets game. They hit the targets, chalking up their first 100% on-time delivery month in the process. Since then delivery performance has continued at or near the 100% on-time level with nary a blip.

Process Changes Improve Performance, Expand Capabilities

On-time delivery isn’t the only performance metric at Thrustmaster that’s moved sharply in the right direction. Costs have declined and order-to-shipment lead times have shrunk. Quality and productivity have both improved, as have profit margins.

These results and other benefits from the application of lean principles have made it easier for Thrustmaster to scale down due to a steep dropoff in its petroleum-related business; globally, these markets were down 60% as of summer 2016. But because of their operational improvements, the company has been able to position itself in new markets (inland waterways, for example) where it can now compete against larger, higher volume manufacturers.

When plant-wide metrics all move in concert it’s a clear sign that lean isn’t limited to a project or area, but is driving a business transformation. In addition to creating the work cells, establishing standard work and moving people out onto the production floor, an impressive array of initiatives have enabled Thrustmaster’s forward progress:

- A3s have become the company’s standard problem-solving methodology.

- Problem-solving boards in each cell report responsibilities and resolution.

- Kaizen teams tackle cross-functional improvement projects.

- A voice-of-the-customer exercise communicated their lean objectives to key customers, and deepened their understanding of Thrustmaster’s key points of customer value.

- A streamlined process has halved the time required for daily performance reviews.

- Purchasing now uses a kanban system to release purchase orders.

- Flow concepts have been extended into billing and after sale product support.

The company’s management system and behaviors continue to evolve. Hoping to improve horizontal alignment of goals and execution, the company has begun to transition to a hoshin-based management system that extends the planning and execution process that started in manufacturing to all departments. Engineering has also done extensive work to value-stream map and streamline their new product development processes.

“In the past our engineers worked to deadlines, at which point they’d report whether they were done or not,” says Small. “The new system set milestones and gateways so that we know if we’re on schedule or behind on a particular project.”

All of these changes would have been impossible without dedicated employees and managers who were willing to learn new ways of working and give them a try. “You really need excellent people,” concludes Bekker when asked to explain the speed of Thrustmaster’s transformation in comparison to other companies. “Businesses are all about money, but companies are all about people. If you don’t have the right people, you’re not going to make it work.”

“It was great visiting every department every day,” says Jason Small, General Manager. “But it took an hour. We’ve reduced our daily meeting times down to 20-25 minutes with the same effectiveness.”

On-Time Delivery

Thrustmaster Box Score

Thrustmaster’s achieved all of its performance improvement targets within 18 months.

- Improved first-pass yield to 90%,

- Increased on-time delivery to at least 90%, and

- Reduced product costs to 100% or less of targets.

Learn More:

- Visit Thrustmaster of Texas

- Montemayor describes how operators reacted to the lean changes in an answer to a question from the audience at the 2016 Lean Transformation Summit: https://vimeo.com/187228765

Co-Learning Partners

To launch its lean transformation Thrustmaster joined Lean Enterprise Institute’s Co-Learning Partnership program. LEI partners with a select group of companies to help them on their lean journeys and jointly conduct experiments. Partner companies get access to LEI thought leaders, such as John Shook, Jim Womack, and Mark Reich, as well as LEI coaches and other experts.

Participants in the partnership program test and apply best practices summarized in LEI’s Lean Transformation Framework. The framework revolves around a series of five questions that will yield greater success and help organizations maintain the lean transformation’s forward momentum.

To learn more about Co-Learning Partnerships, contact Deb McGee at dmcgee@lean.org.